Fig. 1: A depiction of ancient Mesopotamia during its peak.[1]

Many great ancient civilizations flourished in the region known as Mesopotamia; the land between two rivers. Renowned for their lavish architecture and advanced scientific discoveries that forever changed the way we live, the Mesopotamian people who lived thousands of years ago served as the epitome of civilization for countless empires and are still relevant today.[2] However, this great society with its rich culture and intellectual prowess started to decline centuries after its creation and became a forgotten part of history until the 1800s.[3] A cuneiform slab, the iron sword, and the clay tablet known as “Plimpton 322” are the artifacts that effectively communicate the most significant causes that led to the decline of this great ancient civilization. They have been chosen to represent the process of Mesopotamian languages passing into oblivion, a key power shift that took place in the region, and the negative impacts Greek Imperialism had on this civilization.

Cuneiform Slab

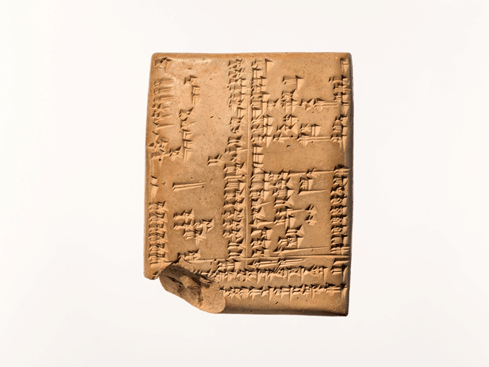

Fig. 2: Bilingual cuneiform clay tablet.[4]

The first contributor to the decline of this ancient civilization will be represented by a bilingual cuneiform slab that was unearthed by archaeologists in Mesopotamian ruins. The decline of the Sumerian and Akkadian languages began under the Assyrian Empire’s reign over Mesopotamia and continued throughout forthcoming Babylonian and Persian empires.[5] Being a language isolate that shared no genealogical relationship with any other ancient language, the cuneiform script was difficult and time consuming to learn.[6] Nonetheless, both spoken languages and cuneiform played important roles in Mesopotamian religion and were used at holy celebrations as well as in the composition of sacred texts.[7] However as the Assyrian Empire gained more influence throughout the Middle East and conquered Mesopotamia, Aramaic became the common language and replaced both Sumerian and Akkadian as the official language.[8] Unlike the complex cuneiform script which contained over 7,000 characters, Aramaic used an easy to learn alphabet that enabled it to prevail for millennia afterwards.[9] The decline of classical Mesopotamian languages and written script significantly contributed to the fall of this great civilization in the way that it resulted in the gradual loss of an important aspect of its unique cultural heritage.

Iron Sword

Fig. 3: Assyrian sword sheath.[10]

Then, the iron sword facilitated an important power shift in Mesopotamia that further accelerated the decline of this great civilization. Tyrannical kings enacted tough policies that altered established traditions and deployed their ruthless armies to take down anyone who rebelled against them.[11] The Assyrian Empire being a most notable example emerged from a militaristic society that maintained a standing army of thousands of professional soldiers, and used the iron sword in battles, which instantly gave them a distinct advantage over enemies.[12] Because retaining control over such a vast empire was a challenge in and of itself, conquered civilians were relocated within the Empire to reduce the chances of them forming rebel alliances.[13] Assyrian kings also built forts and roads throughout their territories to allow their armies to travel to troubled areas quickly and crush rebellions before they got out of hand.[14] Despite these efforts, the ruthlessness of most rulers and their warriors made it all too common for civil wars to erupt throughout the subjugated Mesopotamian region.[15] Internal conflict led to the destruction of iconic Mesopotamian buildings such as ziggurats, and many of the great cities it was famous for.[16] Assyrian rulers’ oppressive policies and violent responses to the concerns voiced by their subjugated population further contributed to the decline of ancient Mesopotamian civilization as innumerable irreplaceable cultural hallmarks were obliterated during this tumultuous era, and much of Mesopotamia’s rich cultural history was erased.

“Plimpton 322” Clay Tablet

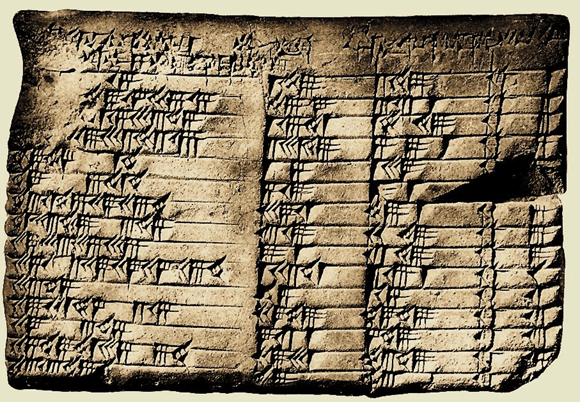

Fig. 4: “Plimpton 322.”[17]

Finally, Greek imperialism was the most significant factor that catalyzed the decline of Mesopotamia and its effects can be observed from examining the clay tablet known as “Plimpton 322”. By the time Alexander the Great of Macedonia had conquered Mesopotamia, there was not much left of the ancient civilization that had once flourished as the world’s cultural and commercial hub.[18] The subjugation of Mesopotamian people and oppressive policies of the Greek Empire including the enslavement of conquered civilians and the seizing of their property effectively contributed to the decline of this civilization as it not only stripped the Mesopotamians of their identity as a distinct society but also cast their rich heritage into oblivion.[19] As this civilization began to decline, its people culturally assimilated with the Greeks and were overshadowed by this new regional superpower.[20] Apart from losing their identity as a unique civilization, the work of Mesopotamian astronomers, scholars, scientists, and intellectuals was also not accredited by Greek intellectuals who plagiarized their advanced discoveries.[21] Modern historians argue however, that because the Greek Empire was made up of multicultural territories, it was only normal that Greek scholars and philosophers would “borrow knowledge” from Mesopotamian culture.[22] Although the term “borrow” is defined in this context as “to take (a word, idea, or method) from another source and use it in one’s own language or work“ many Greek scholars and intellectuals failed to accredit the Mesopotamian individuals whose work they “borrowed”.[23] A well known example is Greek mathematician Pythagoras who is accredited with discovering the Pythagorean Theorem which historians later found on a Babylonian clay tablet that was created 3,700 before Pythagoras’s time.[24] Despite being a clear act of plagiarism, public ignorance has resulted in us continuing to teach and believe that famous Greek scholars like Pythagoras who plagiarized Mesopotamian discoveries were indeed the true pioneers of such advanced concepts. By erasing the names of great Mesopotamian innovators and intellectuals from history through first assimilating Mesopotamians into Hellenistic culture and then plagiarizing their work, Greek Imperialism acted as the most significant factor leading to the decline of one of the greatest civilizations to of have ever existed.

Conclusion

The gradual disappearance of traditional Mesopotamian languages, an important power shift that took place in the region, and Greek imperialism were the most significant contributors to the decline of ancient Mesopotamian civilization, as they lead to the abandonment of important Mesopotamian traditions, the destruction of countless cultural monuments, and to the plagiarism of countless discoveries under Greek imperialists; most notably the Pythagorean Theorem. Despite its fall, the breakthroughs and inventions of this ancient civilization provided the framework upon which innumerable modern scientific and technological innovations have been made, and is why ancient Mesopotamia is still relevant thousands of years after its time.

[1] Deepan Kolad, “Hidden Objects Backgrounds,” Deepan Kolad Latheev, last modified March 11, 2014, https://deepankoladlatheev.blogspot.com/2014/03/blog-post_6161.html.

[2] “Whatever Happened to the Ancient Mesopotamians,” TimeMaps, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.timemaps.com/blog/whatever-happened-to-ancient-mesopotamian-civilization/.

[3] “Assyrian Empire,” Age of Empires, Microsoft, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.ageofempires.com/history/assyrian-culture/.

[4] Creative Commons, “Bilingual Cuneiform Tablet,” Met Museum, accessed March 13, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/321677.

[5] “Whatever Happened to the Ancient Mesopotamians,” TimeMaps, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.timemaps.com/blog/whatever-happened-to-ancient-mesopotamian-civilization/.

[6] Joshua J. Mark, “Cuneiform,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, last modified March 15, 2018, https://www.ancient.eu/cuneiform/.

[7] “Whatever Happened to the Ancient Mesopotamians,” TimeMaps, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.timemaps.com/blog/whatever-happened-to-ancient-mesopotamian-civilization/.

[8] “Whatever Happened to the Ancient Mesopotamians,” TimeMaps, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.timemaps.com/blog/whatever-happened-to-ancient-mesopotamian-civilization/.

[9] “Whatever Happened to the Ancient Mesopotamians,” TimeMaps, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.timemaps.com/blog/whatever-happened-to-ancient-mesopotamian-civilization/.

[10] Osama S. M. Amin, “Assyrian Sword Sheath,” Ancient History Encyclopedia, last modified September 13, 2015. https://www.ancient.eu/image/4072/assyrian-sword-sheath/.

[11] Nelson Ken, “Ancient Mesopotamia: Assyrian Army and Warriors,” Ducksters, Technological Solutions Inc., accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.ducksters.com/history/mesopotamia/assyrian_army.php.

[12] Nelson Ken, “Ancient Mesopotamia: Assyrian Army and Warriors,” Ducksters, Technological Solutions Inc., accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.ducksters.com/history/mesopotamia/assyrian_army.php.

[13] Nelson Ken, “Ancient Mesopotamia: Assyrian Army and Warriors,” Ducksters, Technological Solutions Inc., accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.ducksters.com/history/mesopotamia/assyrian_army.php.

[14] Nelson Ken, “Ancient Mesopotamia: Assyrian Empire,” Ducksters, Technological Solutions Inc., accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.ducksters.com/history/mesopotamia/assyrian_empire.php.

[15] “Assyrian Empire,” Age of Empires, Microsoft, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.ageofempires.com/history/assyrian-culture/.

[16] “Whatever Happened to the Ancient Mesopotamians,” TimeMaps, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.timemaps.com/blog/whatever-happened-to-ancient-mesopotamian-civilization/.

[17] Bill Casselman, “The Babylonian Tablet ‘Plimpton 322,’” Math UBC, accessed March 13, 2020, https://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/courses/m446-03/pl322/pl322.html#refs.

[18] “Whatever Happened to the Ancient Mesopotamians,” TimeMaps, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.timemaps.com/blog/whatever-happened-to-ancient-mesopotamian-civilization/.

[19] “Whatever Happened to the Ancient Mesopotamians,” TimeMaps, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.timemaps.com/blog/whatever-happened-to-ancient-mesopotamian-civilization/.

[20] “Whatever Happened to the Ancient Mesopotamians,” TimeMaps, accessed March 10, 2020, https://www.timemaps.com/blog/whatever-happened-to-ancient-mesopotamian-civilization/.

[21] “Mysterious Clay Tablet Reveals Babylonians Used Trigonometry 1,000 Years before Pythagoras,” Ancient Pages, last modified August 24, 2017, http://www.ancientpages.com/2017/08/24/mysterious-clay-tablet-reveals-babylonians-used-trigonometry-1000-years-pythagoras/.

[22] Charlotte Higgins, “Ancient Greece, the Middle East, and An Ancient Cultural Internet,” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media Limited, last modified July 11, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2013/jul/11/ancient-greece-cultural-hybridisation-theory.

[23] “Mysterious Clay Tablet Reveals Babylonians Used Trigonometry 1,000 Years before Pythagoras,” Ancient Pages, last modified August 24, 2017, http://www.ancientpages.com/2017/08/24/mysterious-clay-tablet-reveals-babylonians-used-trigonometry-1000-years-pythagoras/.

[24] “Mysterious Clay Tablet Reveals Babylonians Used Trigonometry 1,000 Years before Pythagoras,” Ancient Pages, last modified August 24, 2017, http://www.ancientpages.com/2017/08/24/mysterious-clay-tablet-reveals-babylonians-used-trigonometry-1000-years-pythagoras/.

Bibliography

1. Amin, Osama S. M. “Assyrian Sword Sheath.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified September 13, 2015.https://www.ancient.eu/image/4072/assyrian- sword- sheath/.

2. “Assyrian Empire.” Age of Empire. Microsoft, accessed March 10, 2020. https://www.ageofempires.com/history/assyrian-culture/.

3. Casselman, Bill. “The Babylonian Tablet ‘Plimpton 322.’” Math UBC. Accessed March 13, 2020. https://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/courses/m446-03/pl322/pl322.html#refs.

4. Creative Commons, “Bilingual Cuneiform Tablet.” Met Museum. Accessed March 13, 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/321677.

5. Higgins, Charlotte. “Ancient Greece, the Middle East, and an Ancient Cultural Internet.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited, last modified July 11, 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2013/jul/11/ancient-greece-cultural- hybridisation-theory.

6. Ken, Nelson. “Ancient Mesopotamia: Assyrian Army and Warriors.” Ducksters. Technological Solutions Inc., accessed March 10, 2020. https://www.ducksters.com/history/mesopotamia/assyrian_army.php.

7. Ken, Nelson. “Ancient Mesopotamia: Assyrian Empire.” Ducksters. Technological Solutions Inc., accessed March 10, 2020. https://www.ducksters.com/history/mesopotamia/assyrian_empire.php.

8. Kolad, Deepan. “Hidden Objects Backgrounds.” Deepan Kolad Latheev. Last modified March 11, 2014. https://deepankoladlatheev.blogspot.com/2014/03/blog-post_6161.html.

9. Mark, Joshua J. “Cuneiform.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified March 15, 2018. https://www.ancient.eu/cuneiform/.